Pushing Passive: Affordable Housing Forges the Way for High Performance

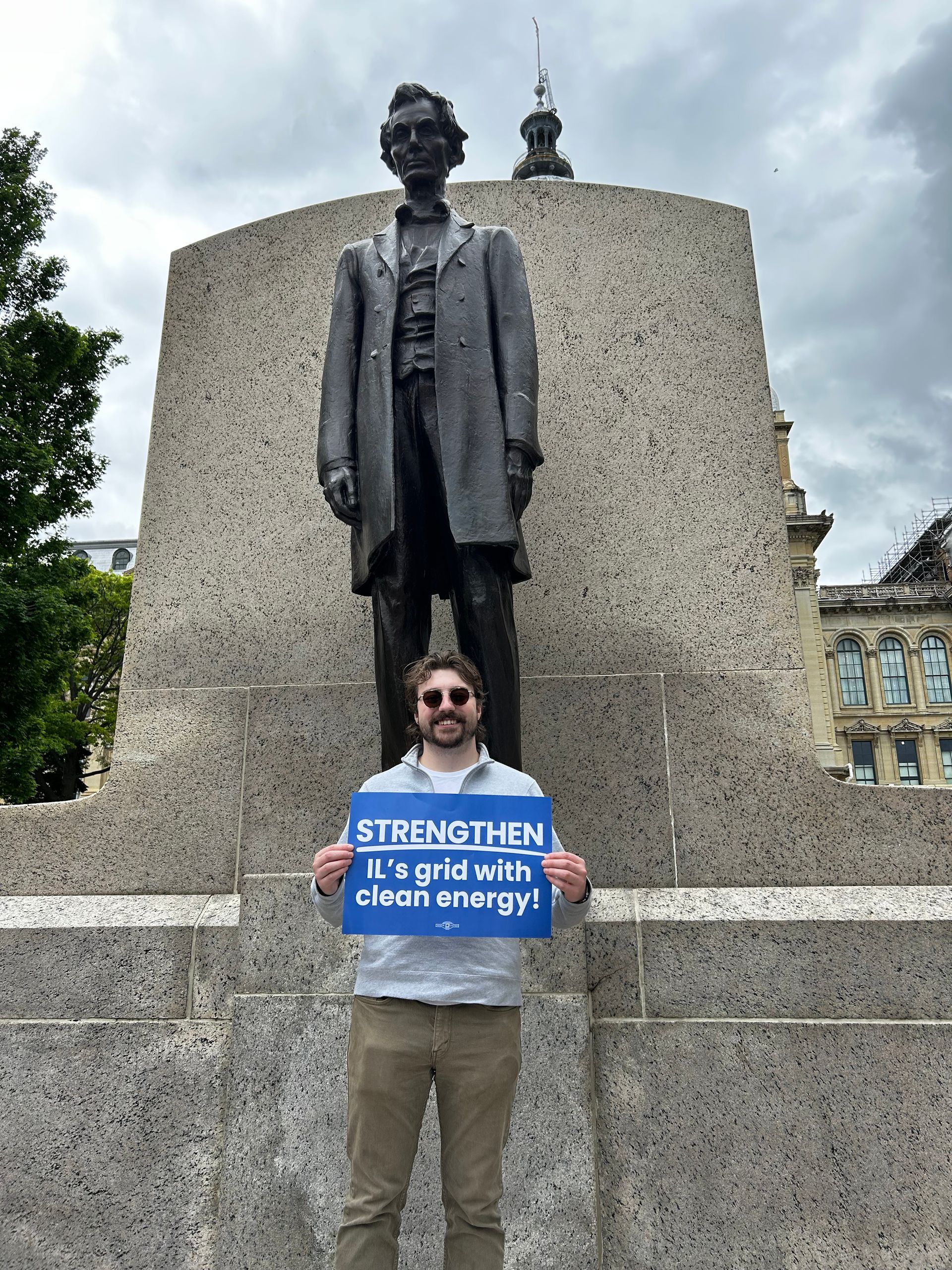

Highlighting many of the best practices at the intersection of green design and affordable housing, The Conservatory Apartments will be one of the largest high-performance, multi-unit residential buildings in the City of Chicago upon completion. While higher construction cost can be an impediment to building sustainable affordable housing, the development team was able to leverage financial incentives to achieve passive house certification through the Passive House Institute of the United States (Phius). By employing several innovative techniques, they maintained a balance between high energy performance and economic efficiency while also providing benefits to the broader community.

On January 25th, Illinois Green Alliance hosted Pushing Passive: Affordable Housing Forges the Way for High Performance. The webinar and tour featured a discussion with Susan King, Principal Architect of HED; Tom Boeman, owner of Boeman Design; and Perry Vietti, President of Interfaith Housing Development Corporation, about their experience building The Conservatory Apartments.

The apartments are located near Garfield Park Conservatory, in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood. They will provide all single resident occupancies (SROs) through Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), with 34 of the units being reserved for individuals who were formerly homeless and the remaining nine units set aside for formerly institutionalized individuals.

“It is for people that have been institutionalized, in most cases inappropriately, and trying to bring them out of the state. The idea is for them to live in the community, not an institution,” Vietti said.

The Conservatory Apartments are blended with services through both Debra’s Place and Trilogy and offer one-year leases. They will be the first passive house certified affordable project and the largest Phius certified multi-family building in Chicago.

Meeting Phius Standards with Economic Trade-offs

Building sustainably can be difficult to achieve financially without the right mix of resources. It cost $13.3 million to build the Conservatory Apartments, but the team was able to achieve economic efficiency in many ways.

The Illinois Housing Development Authority (IHDA), PNC Bank, the City of Chicago, the Federal Home Loan Bank, and ComEd’s energy incentive program provided funding for the project. The site used to be a parking lot for a public school that closed in 2013, so the development team was able to purchase the land for free.

Most importantly, passive housing scores a larger amount of Permanent Supportive Housing “points” for the highly competitive IHDA funding, providing a financial incentive to pursue these standards.

King also explained how the updated 2019 Chicago Construction Code allowed them to build with a wood frame. Wood, as opposed to framing materials like steel and concrete, is readily available and cheaper to purchase, which allowed for a strategic economic trade off.

“The key thing about the new code for us was the fact that it allowed us to build the project in wood…because we’re building in wood frame, we’re [going to] save money, and we’re [going totake that money and get triple glazed windows, the highest efficient system we can get for heating and cooling, and extra installation. We can trade-off the structure for the envelope cost,” King said.

WUFI Model and Envelope Design

The Phius standards are target- and location-specific. They are reliant upon heating demand, cooling demand, and the source energy target—a reflection of how much total energy the building uses. The project team used WUFI software to model its compliance with different standards.

A major challenge the team faced was meeting the energy source target, which they were able to achieve by using on-site renewables like photovoltaics (PV) on the roof. Although they did not pursue them, new financial incentives such as government grants and Green Bonds for renewable energy make it more feasible for future projects to also adopt on-site renewables while maintaining their budget.

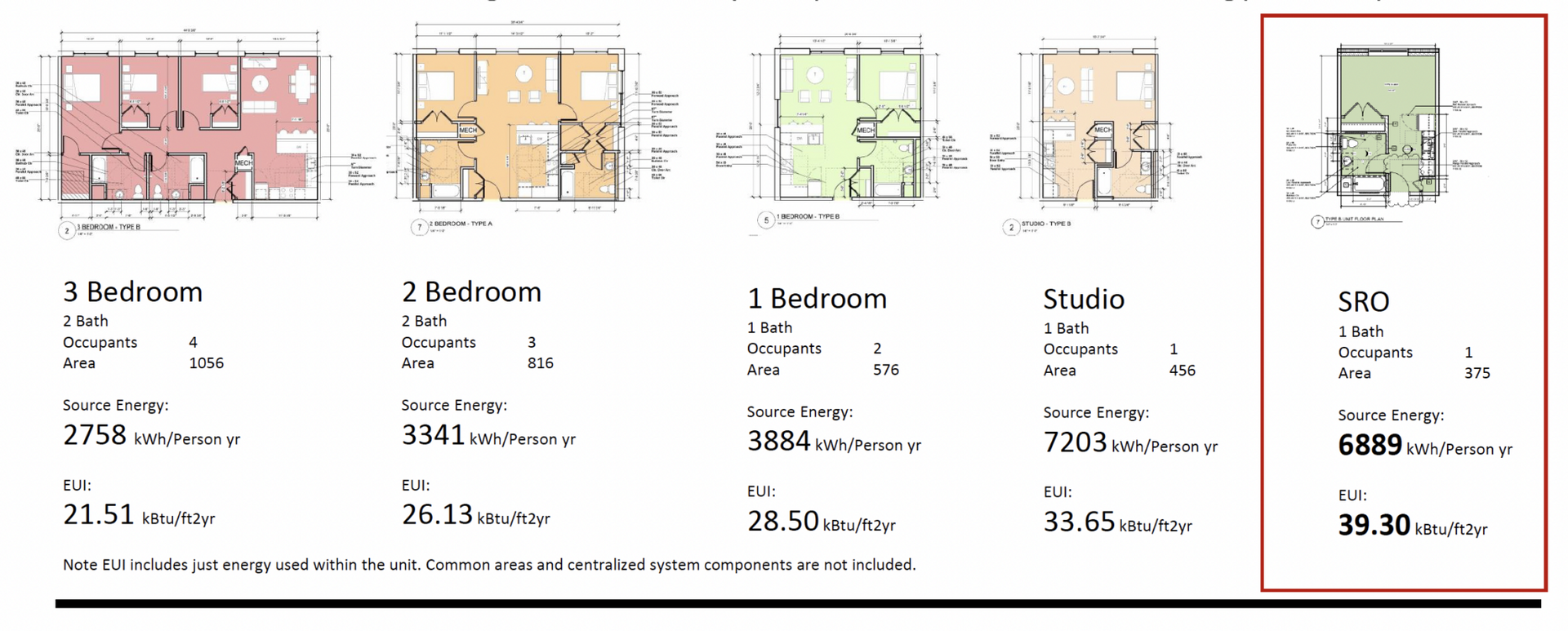

As the Conservatory Apartments are single resident occupancy, the development team had to be wary of being inherently energy dense, as SROs generally have greater ventilation per person and greater appliance density compared to traditional building types. While originally unattainable, Phius acknowledged the realistic energy use of SROs and adjusted their fixed energy targets to compensate for these expectations.

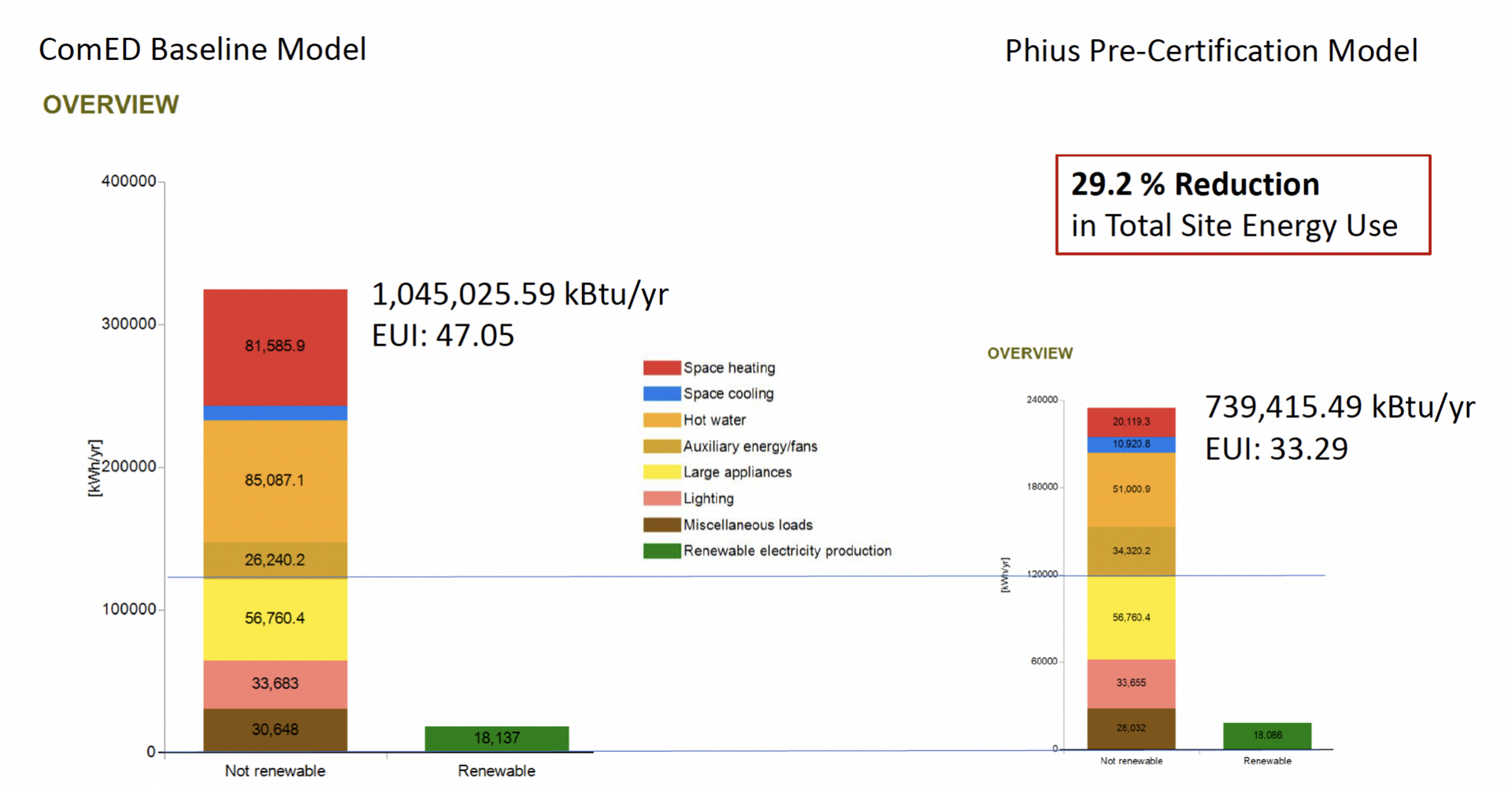

Shown through the WUFI model, the building performed quite well in heat loss and the heating demand balance, with a 52.4% reduction in heat loss because of the thoughtful insulation and energy recovery ventilator (ERV) uses in the envelope design. Compared to the ComEd baseline model, there was a 29.2% reduction in total site energy use, in which heating, cooling, and domestic hot water saw the greatest reductions.

Takeaways

The Conservatory Apartments set an important precedent in demonstrating how it is possible to build affordable housing that is compliant with the net zero Phius standards, while also being economically feasible. In fact, architects, builders, and engineers can be financially incentivized to do so with the right trade-offs.

The development team utilized many methods of efficiency to achieve their high energy performance while also staying within budget:

- Simplifying elevations such as glass finishes aided them in achieving passive house standards.

- Experience is important: For the framing, their subcontractor EDON had experience with passive housing, which was helpful when being tested for the pressurization and depressurization mode of the building.

- The space for PV was maximized on the roof, which was absolutely needed to hit the source target.

- The wall insulation was hybrid, with four inches of rigid foam insulation combined with Batt insulation. Batt was the most economical choice, and the outlet placement in the building allowed for optimal installation practices.

- An exterior insulation finish system (EIFS), a non-load bearing system commonly used with wood frames, was not approved by the Chicago Department of Housing and Development (DPD). Despite being a larger building, the development team realized they did not have to use an EIFS to meet passive house. CUPACLAD, a slate cladding with a rainscreen, was instead used for insulation and weather protection.

- They used the Knight Walls System, a continuous installation system that was also thermally broken—manufactured with an aluminum frame to inhibit conductive thermal energy loss—to save money with cladding.

Although the initial cost of construction may seem daunting, the efforts of King, Boeman, and Vietti have been more than rewarding.

“In conclusion, we can do this, it seems a little bit like we are building a Cadillac, but why shouldn’t we build better?” King said.